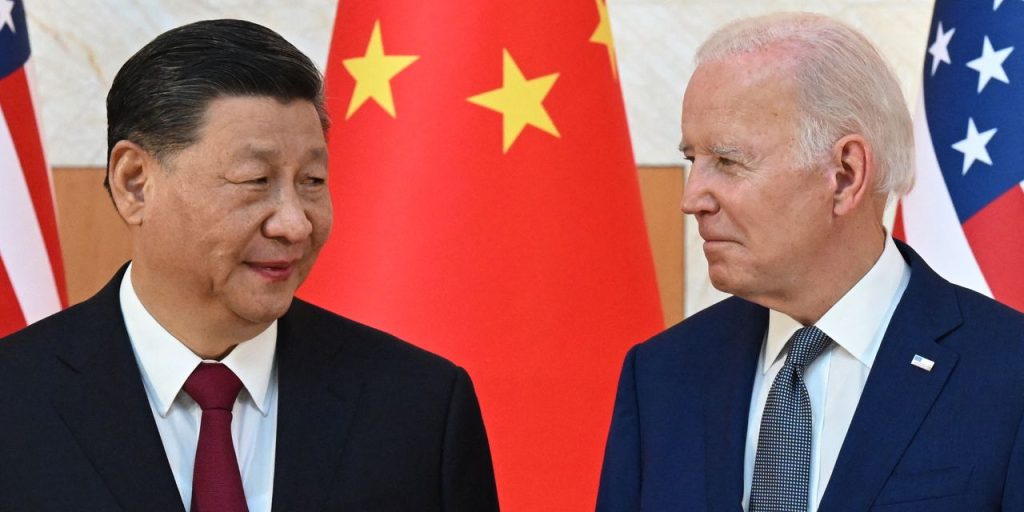

All eyes are on the upcoming leaders’ meeting of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC), to be held in San Francisco Nov. 11-17. And with good reason: there is a distinct possibility that U.S. President Joe Biden and Chinese President Xi Jinping will meet on the sidelines of this pan-regional gathering, exactly one year after their last summit in Bali on the eve of the annual G20 summit.

The Bali meeting accomplished little. While Biden and Xi agreed to set a “floor” for the deteriorating Sino-American relationship, the outcome has been anything but stable. Less than three months after the Bali summit, the U.S. downing of a Chinese surveillance balloon was followed by a temporary freeze in diplomatic engagement, additional sanctions on Chinese technology, and several close calls between the world’s two most powerful militaries. Meanwhile, the U.S. Congress has turned up the heat on China over Taiwan, and Xi accused the United States of implementing “all-around containment.” Some floor!

A Biden-Xi summit now could be a sorely needed second chance. Both sides appear to be hard at work preparing. Unlike the Bali meeting, the San Francisco summit must be scripted for success. With the U.S.-China relationship in serious trouble, and a war-torn world in urgent need of leadership, this summit should pursue three key objectives.

The first is deliverables. Notwithstanding America’s revisionist aversion to engagement with China — in effect, blaming the current conflict on decades of “appeasement” that began when China joined the World Trade Organization in 2001 — it is critical to find common ground on which to re-establish constructive dialogue.

The focus should be less on sloganeering — last year’s “floor” or this year’s “de-risking” — and more on clear and achievable objectives. This could include reopening closed consulates (for example, the U.S. consulate in Chengdu and the Chinese consulate in Houston), relaxing visa requirements, increasing direct air flights (now 24 per week, compared to more than 150 pre-COVID), and restarting popular student exchanges (such as the Fulbright Program).

Improving people-to-people ties — which the two presidents can easily address if they are serious about re-engagement — often leads to reduced political animosity. By reaching for the low-hanging fruit, Biden and Xi could open the door to talks on more contentious topics, such as relaxing constraints on NGOs, the glue that holds societies together, or tackling the fentanyl crisis, in which both countries play a key role.

“The U.S. and China could make a real difference by brokering peace agreements in Ukraine and the Middle East.”

But the most urgent deliverable would be a resumption of regular military-to-military communications, which the Chinese suspended after former U.S. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi visited Taiwan in August 2022. The danger posed by this breakdown in military contacts was glaringly obvious during the balloon fiasco in early February, as well as in recent near-misses between the two superpowers’ warships in the Taiwan Strait and aircraft over the South China Sea. As tensions escalate between two uncommunicative militaries, the risks of accidental conflict are high and rising.

Second, it is also necessary to articulate aspirational goals. A joint statement from Biden and Xi should underscore their shared recognition of two existential threats facing both countries: climate change and global health. Even though U.S. Special Presidential Envoy for Climate John Kerry has met with senior Chinese officials several times this year, collaboration on clean energy has stalled, owing to alleged national-security concerns on both sides. Moreover, progress on global health continues to be stymied by the political theater of the charged debate over the origins of COVID-19.

Of course, a Biden-Xi summit can hardly be expected to resolve these existential problems. But naming them is an important symbolic gesture, evidence of a shared commitment to the collective stewardship of an increasingly precarious world. That is especially the case with the outbreak of the Israel-Hamas war, which risks spilling over into a major regional conflict at the same time that the Ukraine war is at a pivotal moment. The U.S. and China could make a real difference by brokering peace agreements in both wars.

Third, Sino-American relations need a new architecture of engagement. A Biden-Xi meeting at APEC would certainly be a positive development. But annual summits aren’t enough to resolve deep-rooted conflicts between two superpowers.

I have long favored a shift from the personalized diplomacy that occurs during infrequent leader-to-leader meetings to an institutionalized model of engagement that provides a permanent, robust framework for continuous trouble-shooting and problem solving.

My proposal for a U.S.-China Secretariat is one such possibility. Despite the generally positive reception to this idea in China and elsewhere in Asia, American policymakers have shown no interest. In fact, U.S. Representative Mike Gallagher, the Republican Chairman of the new House Select Committee on China, is beating the drum of “zombie engagement,” warning that efforts to reconnect with the Chinese could lead to America’s demise.

At the same time, I am encouraged by the establishment of four new U.S.-Chinese working groups — a result of recent diplomatic efforts. But this is not nearly enough, especially when compared with the 16 active working groups that were established under the umbrella of the Joint Commission on Commerce and Trade, which the Trump administration disbanded in 2017.

Summits between national leaders are often nothing more than media events. Unfortunately, that was the case last year in Bali. Neither the U.S. nor China, to say nothing for the rest of the world, can afford a similarly vacuous outcome this year in San Francisco. The time for collective action is growing short. Any opportunity for Biden and Xi to agree on realistic deliverables, underscore aspirational goals and lay the foundations for a new architecture of engagement must not be squandered.

Stephen S. Roach, a faculty member at Yale University and former chairman of Morgan Stanley Asia, is the author of Unbalanced: The Codependency of America and China (Yale University Press, 2014) and Accidental Conflict: America, China, and the Clash of False Narratives (Yale University Press, 2022).

This commentary was published with the permission of Project Syndicate — A Better Biden-Xi Summit?

Also read: Financial markets worldwide now face a higher chance of extreme events, El-Erian warns

More: Israel-Hamas war could be the tipping point for a fragile financial system

Read the full article here