As the owner of one of the leading companies that moves household goods to Mexico, in addition to being asked about the procedure for importing household goods, I get asked all sorts of questions about what it’s like to live in Mexico, such as:

What’s the weather like?

Answer: Except for the far north-west of Mexico (think: Tijuana and Ensenada, which has weather like San Diego, California) the weather at the beach in Mexico is hot the summer and pretty ideal in the Highlands pretty much all year round.

Will I be killed by cartel members?

Answer: There’s a good chance you won’t. In my entire time in Mexico, I haven’t yet been killed by cartel members, not even once. The same is true for my wife; she’s still alive. And neither of us had any issues with violence, whatsoever, either. Why not? Two reasons: 1) we’re Americans, and as such, we’re a protected class; and 2) more importantly, we have not been involved with the drug trade, also not even once.

Can I have a better lifestyle than I do in the US on the same amount of money?

Answer: Your lifestyle can be much, much better in Mexico for the same amount of money as in the US or Canada.

I also get asked about the healthcare in Mexico and over the last several years, I had some personal experience, but nothing like a surgery where they put you under general anesthetic.

It was Mark Twain who said, “Nothing so focuses the mind as the prospect of being hanged.”

The same could also be said about one’s answer about almost anything in the abstract when the reality is about to happen. Like, for example, giving glib answers about the healthcare in Mexico in the abstract without ever experiencing a more involved surgery oneself.

That was about to change.

How would I answer the question about healthcare after I had a more serious surgery?

Upon hearing that I needed the surgery, would I panic and want to go back to the US?

No, I wouldn’t.

We live about half of the year at Lake Chapala, which has, as a major benefit, the healthcare facilities of Guadalajara about 45 minutes to an hour and a half away, and these facilities are known for their very modern, very high-quality care. It’s one of the reasons why we live here. While I am not an expert, and relative to personal experience (luckily) I can’t speak with authority about the quality of the healthcare in other areas of Mexico, I assume that Mexico City and most of the major expat areas have good quality healthcare, including Merida, in the Yucatan, which is also known for very good care.

When I was growing up in the Los Angeles area, I had an American friend who went to medical school in Guadalajara and then practiced in the US. He was a pretty good doctor, so that was a good sign.

Other good signs were pretty much everything else I heard about the healthcare here, especially for people like you and me.

Why do I write “for people like you and me?”

Because, while in the US, you (likely) and I (certainly) are just average people who get average medical care, whereas in Mexico, we are viewed as part of the upper class, so we get upper class medical care. It may not be fair, but it is true. My main point of bringing this up is that the experience I am about to describe with the Mexican healthcare system is for an upper-class level of care, which is given to almost all expats. Do all Mexicans get this level of care? No, they don’t, just like in the US, if you had to go to a clinic for people with no money, you wouldn’t get Johns Hopkins’ level care, either.

Here is my timeline:

Tuesday, after an awesome pickleball performance: I see a lump and suspect a problem.

Wednesday at 11:30: I show up without an appointment at the local hospital at Lake Chapala, not in Guadalajara.

Wednesday at 11:45: The doctor sees me, and suspects I have a hernia.

Wednesday at noon: They do an ultrasound, which confirms that I have an inguinal hernia, which is the most common in men and especially in men my age.

Wednesday at 12:15: I meet with the doctor to review the result of the ultrasound, which I was already told by the technician doing the ultrasound: I had a hernia.

Wednesday at 12:30: I’m ready to check out. The hospital tells me that the total bill, out of pocket, without insurance, is $1,800 pesos (a little over USD $100).

Wednesday at 12:31: I pay the bill hurriedly and leave the premises before they can change their mind.

Wednesday at 12:32: After comparing what the cost would be in the US, on behalf of my finances, I pause to express thanks again for being in Mexico. It is a good moment.

Wednesday at 9 PM: The doctor at the hospital emails me the ultrasound report.

Thursday at 11:00: I leave a message for my health insurance agent, Andre Bellon.

Thursday at 11:50: Andre calls me back, explains the costs (about equal to my deductible of $100,000 pesos, or a little less than USD $6,000) and different possible procedures and recommends Dr. Valenzuela, who had extremely skillfully performed a minor surgery on my wife a few years earlier. (He was great. There was no scar and I paid him in cash in the lobby of the hospital.)

It turns out that Dr. Valenzuela has privileges at several hospitals in the Guadalajara area and is an expert in robotic surgery. Andre tells me that the machine to do the robotic surgery is at a hospital that is not in network, so there would be around a $15,000 pesos penalty (around USD $900), if I decided to have the robotic surgery.

Thursday at 12:20: I leave a text on WhatsApp for Dr. Valenzuela, along with my ultrasound report.

Thursday at 12:50: Dr. Valenzuela responds and instructs me to make an appointment at his local office at Lake Chapala for Monday at noon where he would meet me there to discuss it.

Monday at noon: Dr. Valenzuela examines me and immediately knows the problem. It turns out that, since he performed my wife’s surgery, given that he had done so many hernia surgeries, he had taken on the name “Dr. Hernia”, and I believe he even copyrighted or registered it in Mexico. Dr. Valenzuela was such an expert that he teaches the procedure to other doctors and had done thousands of them. Another good sign.

Monday at about 12:15 to 12:19: Dr. Valenzuela explains the options, which are pretty much limited to the robotic surgery at the hospital that was out of network and laparoscopic surgery at a hospital that was in network. Dr. Valenzuela tells me that the robotic surgery would not be needed for me, because I hadn’t had other surgeries in the area and mine would be pretty simple (for him). After I explained that Andre had told me that my insurance deductible was probably more than the cost of the surgery, Doctor Valenzuela said that I could just pay him a particular amount less than my deductible of $100,000 pesos and he would pay all the other bills, completely.

Monday at 12:20: I agree to the finances.

Monday at about 12:21: Dr. Valenzuela explains more about how the surgery would be done, including drawings, pictures, a few videos that I didn’t really need to see and an explanation (with pictures of course, and another video I didn’t need to see of it being done) of how they will insert three small tubes through tiny incisions in and around my navel, inflate my abdominal cavity with carbon dioxide so they could see better, push mesh through the tubes, push or pull the hernia back, and attach the mesh on both sides, all with instruments manipulated through the tubes, a camera and a light, and watched on a television screen. The whole thing would take less than 90 minutes, after which, he and the other medical professionals would have lunch and someone else would wheel me back to my room.

Thursday: Our driver Gilberto picks up my wife and me from our home at Lake Chapala and drives us to Hospital Joya in Guadalajara. On their website you can see a picture of the entrance to the hospital with lots of people lined up and a Mariachi band. They probably took this during Covid, because when I arrived, there was close to nobody there, and I didn’t get the serenade, either.

In the lobby, they put me in a wheelchair, I said “Goodbye” to my wife and Gilberto, and they wheeled me up to my room. My first impression of my room was that it was very big, private, and had a couch large enough to sleep on. My second impression was how nice it was that, through the back door, seconds later, emerges my smiling wife who I had left about five minutes earlier, along with Gilberto, holding all my wife’s supplies.

They were going to stay with me in my room.

This is the way it is generally done in Mexico. If you have to stay overnight, so will your family. They get a bed or a big couch and they even get meals. Later, while Dr. Valenzuela would be manipulating instruments into my gassed up abdomen a little down the hall, my wife would take a nice nap on that couch, on top of the sheet and comfy pillow she had brought for just such an occasion.

I wasn’t going to be there overnight, but it was very nice that I had a very big bathroom with nice toiletries (just like you would expect in a nice hotel) with a really nice, big shower, etc. (It was all really nice.)

They had a TV that my wife could watch later from the comfort of the hospital bed I would have vacated while I was having mesh sewn into my body. The monitor had a disconcerting message, but I was pretty certain it was only in reference to the TV signal. (See the picture to the right and up a bit.)

They put the classic hospital robe on me. In succession, I got asked questions by several people who introduced themselves: a very sweet younger doctor with a sweatshirt that read “Brain Washed Generation”, the nurse who would be in charge of me after my operation, the nutritionist, and several other people.

My wife handed out individually packaged cookies and water to the medical staff. Of course, I couldn’t eat or drink anything. Everyone else was well fed and happy.

They put the IVs into my arm.

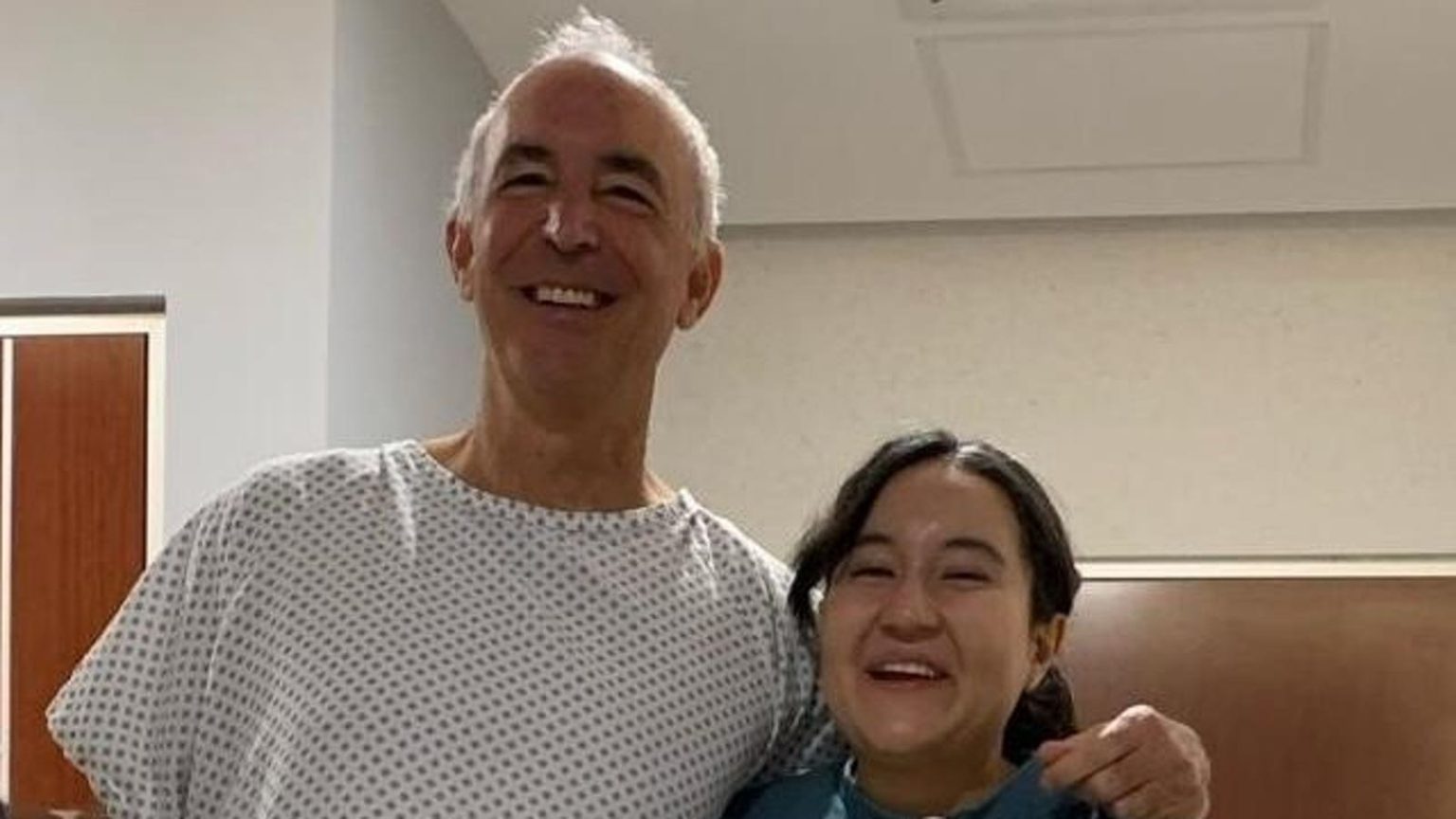

Then, from about three feet away, at the end of my bed, I was treated to the comic spectacle of two of the female nurses trying to put the compression socks on me. They clearly had both technique and determination, but I assume that I was bigger than the average patient, so they had to bring in someone with more upper body strength. After about five minutes, a lot of laughter and a lot of wiggling and pushing and pulling, it was done; the compression socks were on. Fashionable, they are not, but neither was the robe, as you can see for yourself. Everyone rested

and congratulated themselves on a job well done. I don’t remember any high fives, but everyone had a good amount of esprit de corps.

Dr. Valenzuela appeared and we talked for about 60 seconds. He said they were waiting for us. I got put onto another bed, rolled over to just outside the operating room, asked more questions, put onto the bed into the operating room, and asked yet more questions.

Looking up from my bed, in addition to watching the ceiling, tilting my head slightly, I could see that there were perhaps five or six people in the operating room, all busily getting ready for my surgery. They rolled in the monitor they would be watching after they inserted the tubes and pumped me up with gas.

A man who identified himself as the anesthesiologist said hello and told me that I would perhaps feel a bit dizzy in a few seconds.

The next thing I knew, I was talking with my wife about an hour and a half later in my nice, big, private room with the nice toiletries.

I guess it was a good sign that I was hungry, but I didn’t much like what happened next.

My wife and Gilberto wanted dinner. They ordered from the menu, via the hospital phone, like room service at the Four Seasons. They were having a grand time. About 20 minutes later two hamburgers with french fries appeared, one plate for my wife and one plate for Gilberto. They looked really good, and they smelled really good.

However, they didn’t bring me anything, so I was left to wonder what my hamburger would look like.

Maybe a double with some extra crisp pickles, because, after all, I was the one who had the surgery, not my wife or Gilberto.

Finally, they brought in my meal, not yet revealed because the plate had a metal cover. Full of anticipation, I put my finger in the hole in the middle of the metal cover, pulled up and to the right, and looked at what was revealed underneath, on the plate. There it was: slices of cantaloupe and honeydew. Nicely presented, I’ll grant you, in pretty layers. But a hamburger, it was not.

I looked up with a bit of righteous indignation to see my wife was eating french fries and Gilberto had that sort of squinty-eyed look of someone who was really concentrating on enjoying his meal while wiping the catchup from his mouth.

They both smiled and waved, mouths too full with hamburgers and french fries to speak.

After swallowing, my wife asked the staff what they used to season the french Fries, because they were so good.

I ate the fruit.

I don’t remember being in any pain whatsoever; just some mild cramping. In a few hours, they had me walk around the commodious room, and then put me back in the wheelchair for the return trip to the lobby, sans a meaty meal.

Two hours later, Gilberto delivered my wife and me to our home. Four days of vegetarian meals with little or no flower followed, prepared lovingly by my wife, who is very, very good at being creative at making vegetables and fruits as appealing as they can be.

It’s now been three weeks and I am doing very well, albeit a bit sore. I had one post op visit with Dr. Valenzuela in which he did his own ultrasound and verified that everying went well. He also told me that, while he was doing the surgery, he noticed that I had another hernia as well, in my navel.

So, he fixed that one on the way out, no extra charge.

Read the full article here