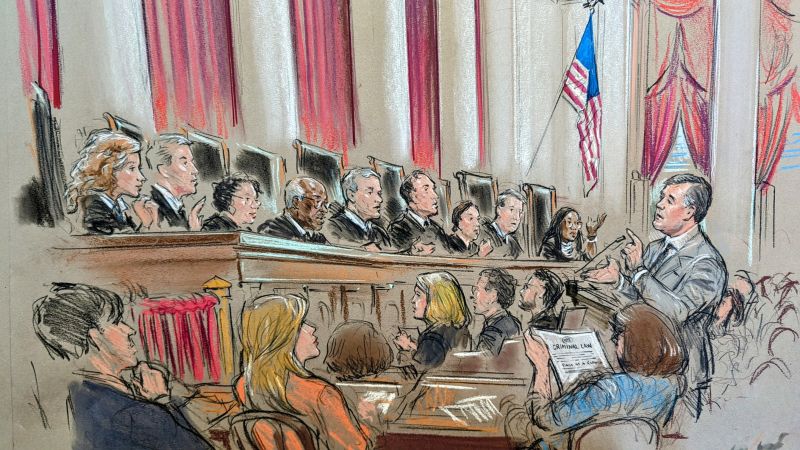

The Supreme Court’s conservative majority indicated Tuesday that it may toss out a charge prosecutors have lodged against hundreds of people who took part in the January 6, 2021, riot on the US Capitol, a decision that could force the Justice Department to reopen some of those cases.

During over 90 minutes of arguments, most justices signaled concern with how the Justice Department is using the law enacted by Congress more than two decades ago in response to the Enron accounting scandal. Critics claimed the felony charge, which carries a prison sentence of up to 20 years, was intended to prevent evidence tampering – not an insurrection in support of a president who lost reelection.

The court’s decision, expected by July, could have significant ramifications for some 350 people who were charged with “obstructing” an official proceeding for their part in the Capitol attack – including more than 100 people who have already been convicted and received prison sentences.

The high court’s ruling could also affect the federal election subversion criminal case pending against former President Donald Trump, who was also charged with the obstruction crime.

Here’s what to know about Tuesday’s oral arguments:

The appeal was brought by a former Pennsylvania police officer, Joseph Fischer, who was charged with multiple crimes for pushing his way into the Capitol after attending Trump’s rally outside the White House on January 6. Fischer’s attorney told the justices that prosecutors overstepped by charging his client with what critics previously framed as an anti-shredding law.

Mostly absent from oral arguments Tuesday was recognition of the traumatic and deadly turn of events that took place just across the street from the Supreme Court three years ago after Trump ginned up a crowd with false claims of fraud and encouraged them to march on the Capitol and “fight like hell.”

Instead, the discussion turned largely on a technical and legalistic debate about the meaning of the words in the law – in particular the word “otherwise.”

That 2002 law makes it a felony to “corruptly” alter, destroy or mutilate a record with the intent of making it unavailable for use in an “official proceeding,” or to “otherwise” obstruct, influence, or impede such a proceeding. Fischer argued that, taken together, the law was geared toward prohibiting records destruction. But the Justice Department said it swept far more broadly than that, encompassing a wider range of actions – including physical intrusion – that would obstruct a proceeding.

“The key word is ‘otherwise,’” Justice Brett Kavanaugh, often a critical vote in high-profile cases, said at one point as he quizzed Solicitor General Elizabeth Prelogar. “It would be odd to have such a broad provision tucked in and connected by the word ‘otherwise.’”

That position seemed to draw attention from Chief Justice John Roberts as well, who at one point sharply pushed back on the government for trying to separate the “evidence” portion of the law from a provision dealing with “obstruction.”

“You can’t just tack it on and say, ‘Look at it as if it’s standing alone,’” Roberts said. “Because it’s not.”

See how the Capitol Riot on January 6 unfolded

Occasionally, Prelogar sought to remind the justices of the details of the case at hand. In one especially pointed response to a question from Kavanaugh about the other charges the DOJ can use in Capitol riot prosecutions, Prelogar argued that Fischer, in advance of the attack, had expressed an intent to storm the Capitol and use violence if necessary to disrupt the vote.

“He said, ‘they can’t vote if they can’t breathe,’” Prelogar argued, referring to Fischer’s texts from before January 6. “And then he went to the Capitol on January 6, with that intent in mind, and took action – including assaulting a law enforcement officer – that did impede the ability of the officers to regain control of the Capitol and let Congress finish its work.”

There was a heavy dose of “whataboutism” from the conservative justices, who repeatedly brought up left-wing protests while pressing both sides about exactly which conduct they believed would – and wouldn’t – be covered by the felony obstruction law.

Justice Neil Gorsuch posed several hypotheticals to Prelogar, asking if prosecutors could use the law to charge someone who participated in a sit-in that disrupted a trial “at a federal courthouse” or who was caught “pulling a fire alarm before a vote” in Congress.

He didn’t mention Rep. Jamaal Bowman by name, but the allusion to the New York Democrat was clear: He pulled the fire alarm shortly before a critical vote on a government funding bill in September. Bowman later pleaded guilty to a misdemeanor offense and was censured by the House.

Justice Samuel Alito brought up the disruptions at the Golden Gate Bridge that occurred Monday. Pro-Palestinian protesters, angry about Israel’s war against Hamas in the Gaza Strip, blocked rush-hour traffic, leading to more than 30 arrests.

“What if something similar to that happened all around the Capitol so that … all the bridges from Virginia were blocked and members from Virginia who needed to appear at a hearing couldn’t get there, or were delayed in getting there?” Alito asked. “Would that be a violation of this provision?”

Prelogar differentiated those cases by pointing out that January 6 was a far more aggressive and multi-pronged assault, with direct aims to shut down a specific proceeding. She said many of the January 6 rioters violently breached multiple police lines, brought tactical gear and weapons, and made explicit threats before arriving in DC.

The Supreme Court’s three liberals appeared to be lined up in favor of the Justice Department’s position that the federal obstruction law is broad enough to include the rioters’ conduct on January 6.

The law, Justice Elena Kagan said, could have been written by Congress to limit its prohibition to evidence tampering. But, she stressed, “it doesn’t do that.”

Kagan and Justices Sonia Sotomayor and Ketanji Brown Jackson pressed Fischer’s attorney, Jeffrey Green, on the plain text of the law – embracing a conservative notion of “textualism,” or reading the law for its plain meaning without considering legislative history and other factors.

Jackson noted that the language in the statute “does not use the term ‘evidence’” but rather “uses the term ‘official proceeding,’” which is defined as including a congressional proceeding.

Though Trump is not a party in the case, the appeal indirectly thrust him onto the Supreme Court’s docket for the third time this election year. In March, the justices unanimously ruled that the former president should appear on the ballot in Colorado despite claims he violated the 14th Amendment’s “insurrectionist ban” because of his actions on January 6.

Special counsel Jack Smith has charged Trump with the same obstruction crime prosecutors filed against Fischer and more than 350 others involved in the attack. The former president and presumptive GOP nominee would almost certainly use a win for Fischer to try to further undermine the Justice Department’s prosecution of the January 6 defendants.

How much Fischer’s case would spill over to Trump’s is open for debate. Smith has argued that the obstruction charge against Trump is based on the fake slate of electors the former president attempted to have submitted to Congress, not the riot itself. Unless the court rules broadly in a way that undermines the charge entirely, the case against Trump may still stick even if Fischer wins his case.

Justice Clarence Thomas was absent from oral arguments on Monday, with the court refusing to explain his absence. He was back on Tuesday for a case that critics say he shouldn’t be involved in at all.

The Fischer case has prompted some liberal critics of the court to demand that Thomas recuse himself. That’s because Thomas’ wife, Ginni Thomas, attended Trump’s incendiary rally on January 6 and plotted with Trump allies on ways to keep him in power after he lost the election.

Thomas has ignored the requests to recuse and posed a number of questions that challenged both sides in the case.

“There have been many violent protests that have interfered with proceedings,” Thomas asked Prelogar, pressing on a theme he returned to repeatedly during the arguments. “Has the government applied this provision to other protests in the past?”

Prelogar said the Justice Department has applied the law more broadly than in evidence tampering cases but acknowledged it has not been used previously against “a situation where people have violently stormed” a building. But that, she said, was based on the unusual nature of the Capitol attack itself.

“I’m not aware,” she said, “of that circumstance ever happening prior to January 6.”

Read the full article here