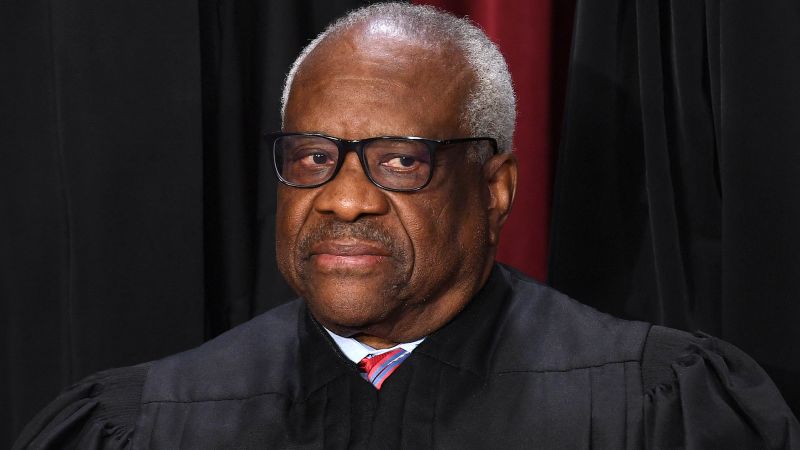

The recent revelations of lavish gifts and travel that a Republican megadonor showered on Justice Clarence Thomas reflect a larger Supreme Court culture of nondisclosure, little explanation, and no comment.

The justices have provided less and less information regarding travel and gifts on their annual financial disclosure forms over the years. Earlier in the 2000s, for example, Thomas listed some private-plane travel similar in nature to some of the trips he later withheld which were detailed in a ProPublica report last week.

In a brief statement responding to the story of his relationship with billionaire real estate magnate Harlan Crow, Thomas said his colleagues and others in the judiciary had advised that he need not report “this sort of hospitality from close personal friends, who did not have business before the Court.” He did not reveal with whom he had conferred or whether Chief Justice John Roberts, who declined to comment, was consulted.

The incident reflects the broader lack of accountability at the high court regarding off-bench behavior. Justices regularly brush aside reporters’ queries for specifics on travel and gifts, book advances and other extracurricular activities.

They have repeatedly spurned calls by members of Congress that they adopt a formal ethics code. Senate Judiciary Committee Chairman Dick Durbin made another such plea to Roberts this week as he also urged the chief justice to open an investigation into Thomas’ conduct.

At the same time, the high court has long benefited from a certain degree of good will, free of the scrutiny watchdog groups and news media have given the legislative and executive branches of government.

They may have squandered that good will.

Polls show the public approval of the court – now controlled by a conservative supermajority – plunging. The pattern was accelerated after last summer’s reversal of longstanding precedent in multiple cases, most notably the decision dissolving nearly a half century of abortion rights precedent.

The justices’ outside activities have increasingly been in the spotlight as they’ve dithered on whether to adopt a formal code of conduct that applies to lower federal court judges.

They have been discussing such a code, at least back to May 2019 when Justice Elena Kagan told a congressional committee that Roberts was in the process of developing a formal policy for the justices. “It’s something that is being thought very seriously about,” Kagan said at the time.

The court’s Public Information Office has declined to provide any update on the status of possible discussions related to court ethics.

The justices are covered by federal law regarding annual financial disclosures and a requirement that they disqualify themselves from a case when their “impartiality might reasonably be questioned,” but they are exempt from a broader judicial code of conduct that applies to lower court judges.

There is also no process for receiving and resolving complaints against justices, as exists for judges on US district and regional appellate benches. If ethics complaints are lodged against a lower court jurist who is being elevated to the Supreme Court, those complaints will be dismissed when he or she becomes a justice, as happened in 2018 with Brett Kavanaugh.

The annual financial disclosure forms contain investments, other income (such as from lectures and books) and information about gifts and reimbursements for travel and lodging. The specifics of those categories, including whether spouses also went along, have thinned over the decades.

Gabe Roth of the watchdog group Fix the Court said that while fewer specifics have appeared on the public forms over the past two decades, there has long been an internal inconsistency among filings from the nine justices.

Some justices appeared to reveal more, some less, and no mechanism exists to ensure compliance.

Roberts, who became chief justice in 2005, has continually described the high court as beyond the realm of politics and worthy of public trust.

“I think the most import thing for the public to understand is that we are not a political branch of government,” he said in a 2009 C-SPAN interview. “They don’t elect us. If they don’t like what we’re doing, it’s more or less just too bad.”

He noted that the only way to remove a justice is through impeachment by the US House of Representatives and Senate conviction.

Two years later, in an annual report, Roberts offered his most extensive comments to date about potential conflicts of interest among the nine justices and when they decide to recuse themselves, that is, sit out a case because of a potential conflict of interest.

“I have complete confidence in the capability of my colleagues to determine when recusal is warranted,” Roberts wrote. “They are jurists of exceptional integrity and experience whose character and fitness have been examined through a rigorous appointment and confirmation process. … We are all deeply committed to the common interest in preserving the Court’s vital role as an impartial tribunal governed by the rule of law.”

While the chief justice sits atop the federal judiciary, he has no real authority over his eight colleagues. And he has said the court “does not sit in judgment of” its own members.

Just as Roberts declined to respond to the ProPublica report about Thomas’ travel on Crow’s private jet and superyacht, he refused questions last year regarding news reports of evangelical leaders who tried to influence justices with dinners and entertainment.

After the April 6 ProPublica report about the luxurious travel Crow provided Thomas and his wife, Ginni, several members of Congress and critics again called on Chief Justice Roberts to act.

Twenty-four Democratic members of Congress, led by Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse and Rep. Hank Johnson, who chair committees overseeing the federal courts, urged Roberts to undertake a, “swift, thorough, independent and transparent investigation” into whether Thomas violated any laws or ethics rules.

Separately, Durbin said in his Monday letter, joined by fellow Democrats from the Senate Judiciary Committee, that members want to ensure “that the nation’s highest court does not have the federal judiciary’s lowest ethical standards.”

Such rhetoric, unaccompanied in this episode by any Republican outcry, has simply faded in the past.

As Roberts has observed, there is little leverage against life-time appointees. And he and his colleagues continue to act as if they are above it all.

If any of the justices finds this state of affairs concerning, they have not made it public.

One could imagine that at some point a justice might consider the mantra of Roberts himself, memorably uttered as he dissented from the bench in 2015 on a separate matter: “Just who do we think we are?”

Read the full article here