With hundreds of products and dozens of stakeholders, designing a home is a very imprecise science, most notably when it comes to the home’s actual operational performance.

I recently reported on an 86-home community in Florida developed by Pearl Homes where homeowners expected to generate 98% of the power that they would then be consuming. But, after tracking 3 months of operations in 12 of the homes, the performance proved to go well beyond expectations.

Going Beyond Standards

“The results show that we have generated more power than our projections, and we have reduced our power consumption,” said Marshall Gobuty, the president and founder of Pearl Homes. “Both of these are significant outcomes that demonstrate our home is actually net positive, and not a one-off, but could be a replicable process for all residential projects in the U.S.”

The performance difference is significant. Original projections, done with the University of Central Florida’s energy research center FSEC, indicated that 22% of kilowatt hours (kWh) would be exported to the grid across all of the project’s lots; however, the actual performance reports show that up to 57% is exported.

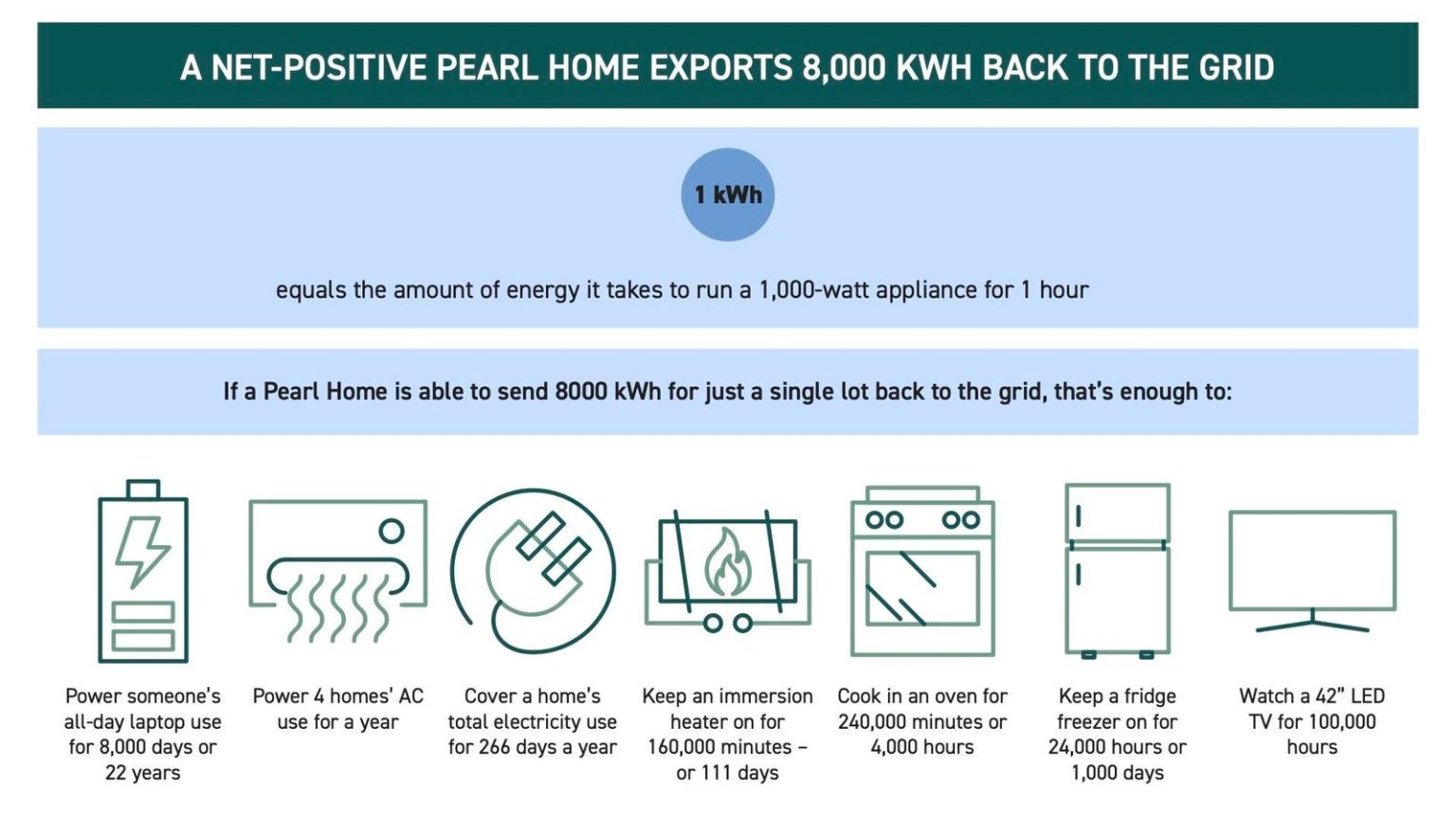

“Showing 57% is unprecedented and it means that we exported 8,000 kWh back to the grid,” Gobuty said. “This includes Tesla car charges and pools, which were not part of our original projection. Even then, we’re still beating our estimates by a long shot.”

So, a net positive home in Hunters Point can send 8,000 kWh back to the grid, equating to enough kWh to power the average home’s total electricity use for 266 days or to power a whole year of air conditioning usage for four homes.

Understanding the Design

While an amazing result for this project, these discrepancies in the design highlight some major challenges for the industry, and at the same time, provide a great runway for learning and improvement.

Let’s start with the challenges. First, home buyers want to be able to understand and trust the information regarding the performance of a home that they are going to purchase, and as the industry stands, there is no way of doing that consistently. This alone is a huge missed opportunity for pull through demand.

“Younger generations are starting to think about the long term cost of home ownership and homeowner value,” said Sara Gutterman, CEO at Green Builder Media who has been sharing generational interest in green homes to better inform builders. “Now, given where energy costs are, there is a higher level of awareness in being cost effective and this is a very easy selling point for today’s home buyers.”

Builders also have to be committed to better performance, but have different motivations.

“Builders are interested in the value it adds to their company or projects on the back end,” Gutterman added. “The cost of green monitoring or certification is fairly nominal considering the ROI, which can be the proof point to then be able to offer that added value to buyers.”

The challenge for builders then becomes an endless aisle of energy rating systems to choose from and not one that is required and not two that operate the same way.

“Just in ESG measurement alone, we are tracking almost two dozen different programs, so there is not a standard in the industry that I see,” said Eric Holt, assistant professor at University of Denver’s Franklin L. Burns School of Real Estate and Construction Management who is doing research for the ESG for Building working group’s Defining Principles to be released later this year. “Even with energy, some are based off of square footage, some on material pieces on different modeling parameters that are not consistent across the industry.”

On top of that, Gutterman and Holt agree that a user can skew the numbers within the various modeling and rating systems.

“It’s a little bit of an art and a science because with some platforms you can enter the data in different ways to get different results,” Gutterman said.

She attributes the slow adoption of energy modeling on the front end and energy certification on the back end to the lack of buy-in from the critical stakeholders, like builders. While investors are creating demand, builders’ resistance to change and hesitancy to learn new things is slowing adoption.

“The absence of one standard tool is good and bad,” she said. “It allows builders to choose what best fits them and they aren’t forced into something that is prescriptive and that they have to use. At the same time, the downfall is that they aren’t forced into using something.”

Pearl Homes has readily adopted the process, and pulled in trusted experts to do the energy modeling. Gary Carmack, the energy development officer at Pearl Homes, said that the difference between the energy modeling that FSEC did for the company’s Hunters Point project and the improved numbers provided from actual performance was the battery.

“The FSEC software for modeling didn’t take into account what the battery could do, which is why the model was different from the actual,” he said. “The battery was the unknown variable.”

The Power of Solar Energy and Local Cooperation

Project partner Blake Richetta, who is the chairman and CEO of the US Subsidiary of global energy storage company sonnen, explains that the value of solar in this project is enhanced by a network of batteries throughout the community.

The main reason that a network of batteries adds significant value to a solar community, he explains, is that batteries transform intermittent, erratic solar energy generation into a true grid asset that can then be capable of replacing power plants.

The community of batteries can harvest solar energy during the solar production hours of the day and run on harvested solar during peak grid consumption evening hours.

“A typical Hunters Point home is generating and storing enough solar energy during solar production hours, to energize the home for approximately nine evening hours. This is far higher than the average home solar battery system,” Richetta said. “This process of intelligently directing solar to a specific time frame reduces grid strain and reduces CO2 emissions more than solar without a battery system, because it relieves the grid of load during the most critical energy usage times of the day when peaking power plants are often deployed, and that typically produce the highest amount of CO2 emissions in the energy system.”

At Hunters Point, the team wants to convert a standard energy system design for master planned communities into a truly renewable system, by producing and storing energy, and then dispatching energy during specific times of the day. Hunters Point aims to become a blueprint for a highly efficient renewable energy based grid.

The three-month performance report from Hunters Point shows how efficient the 12 homes are and how much energy is being injected into the grid.

“This method of storing and redirecting solar to offset specific periods of grid congestion, at the master planned community level, prevents certain investments in grid infrastructure upgrades, and is also referred to as a distribution system investment deferral,” Richetta said. “And, it is a critical component of grid capacity management, in an increasingly renewables-based grid.”

Since this changes the dynamics of the grid, the local cooperation of energy providers makes a big difference.

“Some utilities are more involved and engaged, like in California, Colorado and Minnesota,” Gutterman said. “Some are evolving to be more engaged, and some are more aggressive to offer incentives or rebates to reduce energy demand. However, in certain areas of the country, like central Florida, there are some that require that builders pay for gas hook ups and then pay extra if they want to try to go all electric.”

Richetta cites the Wattsmart Program from Rocky Mountain Power in Utah where there is substantial leadership and cooperation from the utility, which allows them to bring more value to the users. In Florida, at Hunters Point, it has been a different story.

“We would be absolutely delighted to cooperate with FPL on this case study, which would be very significant for them and their energy transition,” he said.

Getting to Scale

Gobuty isn’t in this to promote or sell his homes. He wants to share this community’s performance with national builders to educate them.

“Builders need to shift from selling finishes to selling a solar system,” he said. “Starting in smaller communities, every home is getting better. The better the results, the more people hear about it.”

He wants to bring more trust to the consumer by adding stickers on the homes that show the HERS rating, similar to the sticker found on a new car.

The builder first planned to offer the batteries and solar panels through the homeowners’ association, which would own, lease and monetize the batteries, along with the energy push through to the grid. He thought this type of program would be appealing to home buyers because they could feel good about doing the right thing, in addition to being rewarded for it.

Pearl Homes is also starting a net zero, LEED certified multifamily project in Bradenton, FL, called The Met.

“We need sustainable clean energy in homes as an everyday issue,” he said. “It’s not a money issue, it’s a decision to do the right thing.”

Read the full article here